Introduction

Learning to Program can be an intimidating venture. Not only is there a plethora of programming languages, libraries, frameworks, text editors, and more, there is also the overwhelming amount of opinions amongst more experienced programmers one might consider when deciding between which of these tools is best. Navigating all of this is no easy task and it is something I still struggle with when examining a field of software development I have little knowledge of (pretty much all of it).

How does one know which text editor to choose? Which programming language should I learn first? Should I use MacOS or Windows? (hint: neither). One of the more uncommon (although not necessarily rare) questions asked amongst beginner developers is, which shell should I use?

Before I dive into this topic, I feel like it may be prudent to address the simple question of:

What Is A Shell?

If you have done any amount of beginner programming, systems administration, database management, or other computer related work, it is likely you have already interacted with the Terminal (Emulator), The Command Line and its close companion, The Shell. I shall very briefly address what each of these are, and why, together, they are the most important tool for anyone interested in interacting with computers at any meaningful level.

In Windows, it is known as The Command Prompt (or Powershell), in MacOS it is known as the Terminal, and in Linux and BSD, it is also known simply as the Terminal. The history of the Terminal is extensive, and I would only be doing you a disservice were I to attempt to explain it in depth to you. For the sake of brevity, I shall simply explain how The Command Line and Shell pertain to you, the prospective Computer Programmer, and why it is so important for all programmers to become familiar with it.

If you were to open up Command Prompt in Windows, or the Terminal in MacOS, you would be presented with a black (or blue) colored screen, usually prefaced by a series of characters known as a prompt, and a cursor indicating the program is awaiting you to type something (to provide input via the keyboard). To the uninitiated, this is intimidating, especially after inputting something and getting a mean looking error message (oftentimes highlighted in red). I must admit, whenever anyone who is unfamiliar with computers has seen me working in the Terminal, they have often thrown around terms like "hacker," which I find to be so funny, because it simply shows how the mainstream media has failed to portray technology in an accurate light (save for modern exceptions like Mr. Robot, Halt and Catch Fire, and Silicon Valley). Although hackers do indeed use the command line, so do nearly all computer related professions!

When I first began programming, I started focusing mainly on the tool of the text editor. It was only when I began to seriously dive into the world of Linux that I began to play around in the Terminal. Even in my earliest days playing around in Linux, however, I rarely interacted with the Terminal. This is partially because for at least some time at the beginning, typing in the Shell felt laborious, more boring than programming (which it still is), and not worth investigating beyond the few times I had to invoke a command, or start a program. And it's true that the Shell is just a tool that allows you to invoke commands that call other programs...but that's why it will always be one of the best pieces of software ever written.

Just like everything in the world of programming, there is rarely just one option when it comes to tools, and almost never just one way to do things. The same is true of Shells, but just like these other aspects of the programming world, it doesn't mean there haven't been some clear winners in that space as well.

Although I know I will get some push back on this from Windows Users, it simply is the case that the UNIX-style Shell won out. Specifically the BASH Shell is the one most utilized by default in nearly all Linux Distributions, and was also the primary Shell utilized in MacOS until recently (which currently utilizes the Z Shell). Regardless of which Shell you utilize, many of them have similar commands that perform a plethora of operations via your operating system. It is due to this common history with the BASH Shell, and the features that are available specifically within the BASH Shell scripting language, that it is worthwhile to dive deep into the subject of the Shell and Shell scripting, as it is your direct link to working on and with the operating system while utilizing a high level language to do so. BASH, while not a full featured programming language, is an extremely powerful scripting language which owes its (somewhat niche) popularity to the simple fact that GNU/Linux is everywhere, and thusly, so is its default Shell, bash. Indeed, it is due to the basic UNIX toolset and the eventual choice by the maintainers of GNU/Linux, BSD, and MacOS that BASH proliferated.

At this point in the article I will digress on the subject of scripting, as a beginner is best suited to learning a few basic commands, understanding some of BASH's basic features, and how the use of the Terminal in programming is essential. Please note that while you can follow along in Windows, I will not be covering Windows specific Powershell commands. Unfortunately Windows does not have BASH in its software suite by default, and you must install Windows SubSystem For Linux or Cygwin to utilize many of the same commands.

Following the instructions below, note the effects.

#opening_a_terminal.txt

- MacOS - Click the Launchpad Icon in the Dock, type Terminal and click Terminal

- Linux/BSD - Look up which Terminal Emulator your distribution uses by default and open itYou will be presented with a simple black, amber, or blue colored window with a prompt ending in either % or $ (ZSH uses %, BASH uses $). There is also usually a rectangular cursor indicating the Shell is awaiting input from you. Typing just anything into the Terminal and getting error messages gets old quick, so let's explore our first command, ls:

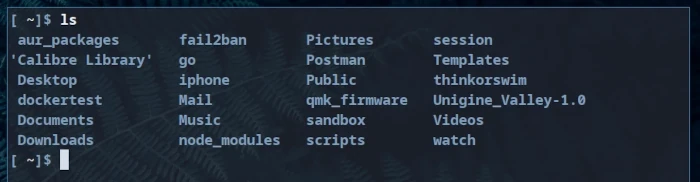

Colloquially, each command will, in theory, be an abbreviation or shortened anagram for a word that will remind you of the action often associated with the command. In this case ls stands simply for 'list' as in 'list all my files and directories'. Here you can see that when I type in ls, I am presented with the contents of what is known as my $HOME directory (we'll cover the $ later). Usually, the ls command has been slightly modified so that colors appear on some of the results, indicating the type of file the result is, or whether or not the result is a directory.

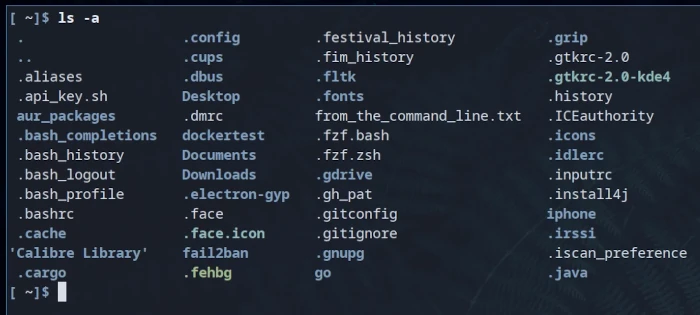

If we then, for our second command, type 'ls' again, but this time follow it with a '-a', we are presented with slightly different results:

Here we see that we now have alot more files and directories, many preceded with a '.', which are our 'hidden' files and directories. There have been more than a few discussions on the concept of hidden files, but needless to say, these files/directories are not visible without the '-a' appended to our 'ls' command. I point this out more as an introduction to the concept of flags '-a' is considered a flag of the 'ls' command that changes the results in some fashion. In this case it stands for 'all', as in show 'list all of my files, yes even the hidden ones.'

Many commands, although not all commands, have flags which somehow change the behavior of the program being called.

I won't go into all the commands available in the Shell as there are quite a lot, but I will provide you with some standard commands to research and become familiar with, as they will become invaluable later on:

#basic_shell_commands.txt

- man

- cd

- mkdir/rmdir

- touch/rm

- cp

- mv

- mv

- echo/print/printf&#- cat/tac

- less

- head

- read

- find

- sed

- grep

- awk

- tr

- df

- top

- ps

- diff

- dd

- whoNow, all of these tools are great, but lack luster by comparison to your standard Graphical User Interface (GUI) programs that most users interact with on their desktops. The power of the Shell isn't in that it can execute programs (although that is its main purpose), it is its ability to chain together and redirect and manipulate the input and output of various programs to yield a desired result...that's right, the BASH Shell is a scripting language, which with the use of various operators can chain together to manipulate textual inputs and outputs. Take this simple example:

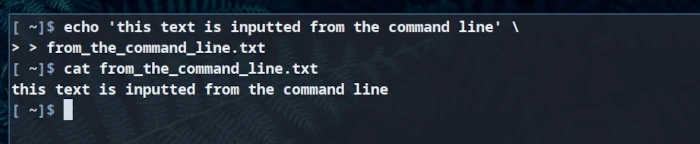

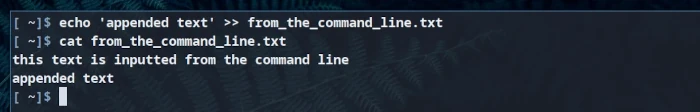

#bash shell

[ ~]$ echo \

"this text is inputted from the command line" \

> from_the_command_line.txtHere we simultaneously created a file called 'from_the_command_line.txt' and wrote the text 'this text is inputted from the command line' into it. If we then inspect the contents of this file using cat:

#bash shell

[ ~]$ cat from_the_command_line.txt

We'll see that indeed, the text 'this text is inputted from the command line' is indeed there. What is happening here?

Redirection Basics

Well just like every problem in programming, we divide the program up into sizeable chunks, and explain each part to the best of our abilities (and hopefully our peers very kindly correct us if we are wrong).

Firstly, what does echo do? Well if you researched my list up above a bit, you'll know that the first recommended command was the 'man' command. Why? well it's the manual of course! Any command you wish to know more about can be investigated by invoking 'man' before the command you wish to know more about, if you type:

#bash shell

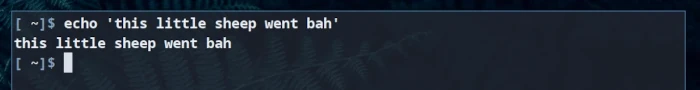

[ ~]$ man echoYou'll see an extensive explanation of the 'echo' command and its various flags. A relatively easy to understand program, echo simply displays any text following the command back to you. So the input that was entered after the 'echo' command is also the output of the command. Thusly invoking:

#bash shell

[ ~]$ echo 'this litle sheep went bah'Displays:

But what about the '>' character in our initial example? Well this is what is known as a redirection operator. This '>' will 'redirect' whatever is the output of the first command (echo) as the input written to the following file or program. Please note that this will overwrite any existing text already present in the file, so don't experiment on any file with valuable information to you. If you do wish to append to the file, without overwriting its existing text, simply double up on the greater than symbol:

#bash shell

[ ~]$ echo 'appended text' >> from_the_command_line.txt

If you wish to research one of the most powerful operators in bash, research the pipe ('|') operator!

Hopefully at this point, you are starting to understand the role of the Shell and the command line a bit better. For this next example, I am going to demonstrate how many programs have a command line interface with which one may interact, or at least initialize, a program, be it a Graphical or Terminal based application.

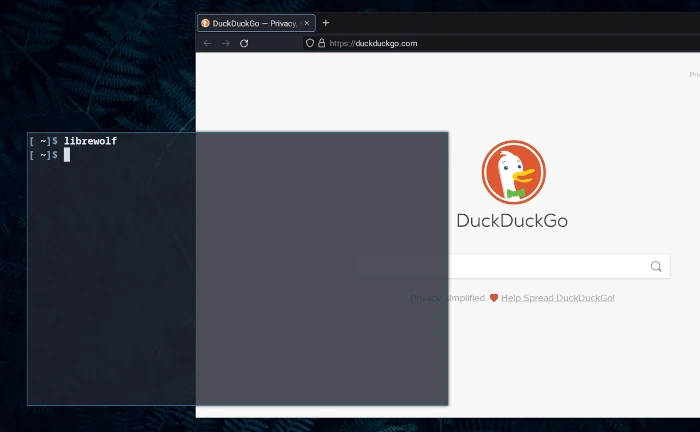

The Power Of The Shell

One of the first epiphanies for me regarding the Terminal was when I realized I could invoke pretty much any program in my operating system with simple commands. If I wished to open my browser (librewolf), I simply had to type into the Terminal its name:

While this may not seem like a big deal to some, it was upon doing this that I realized why the Terminal was powerful, it allowed any program to be invoked as long as you knew its name. Rather than clicking through a myriad of nested directories to find where I had put an executable (like when using Windows File Explorer), I simply had to type it out and it would open up on my screen.

When I first installed Linux, the first piece of graphical software I had become familiar with was the backup utility, Timeshift, which essentially takes a 'snapshot' of the current state of your desktop and allows you to 'revert' back to that snapshot should you want/need to.

Timeshift has both a Graphical User Interface(GUI) as well as a Command Line Interface(CLI). I first learned to use Timeshift utilizing the GUI, but then I became curiouos about the CLI. It wasn't long before I realized that most of the information available via the GUI interface could be accessed via the CLI. I really only needed four commands from the CLI, these were:

#timeshift_commands.txt

- timeshift --create

- timeshift --delete

- timeshift --list

- timeshift --restoreAnd every once in a while, after an update on my system, I would invoke the 'timeshift create' command to create a snapshot of my current system. Timeshift has occasionally saved me from big mistakes I've made, and is a good piece of software.

The reason I point this out is that even though timeshift isn't a part of the Shell as a subject, I am simply pointing it out as a practical example of when utilizing the text interface of Timeshift's CLI, via the Shell, became more useful to me than interfacing with the GUI version. This became even more the case when I discovered the existence of Shell aliases.

A Rose By Any Other Name

Of course, I've provided you now with the knowledge of how to do your own research regarding any command, so be sure to pull up:

#bash shell

[ ~]$ man aliasAnd do more research, but I'll give you a general idea of why this is such a powerful tool for anyone invested in computers to know. Essentially aliases are a series of commands invoked by a custom command of your naming.

If you invoke:

#bash shell

[ ~]$ alias cdls="cd ~/Documents & ls"You will navigate into your Documents directory and then list out its contents after invoking your custom command, 'cdls'

The "&" is another operator that waits for one command to complete before then invoking the following command. The "&" operator can be chained as many times as desired and when applied to an alias, essentially condenses a very long command into a shorter command (unless you name your alias something very long I suppose).

Now, the somewhat annoying thing is that these aliases, when created this way, are forgotten as soon as you close the Terminal or your Shell session somehow ends. Aliases can be saved, however, by placing them in your ~/.bashrc file. This configuration file is checked by the Shell prior to initiation, including alias assignments. Thusly, if you simply append:

#.bashrc

#!/usr/bin/env bash

alias cdls="cd ~/Documents & ls"To the end of your ~/.bashrc file, you will have created a custom command that persists even after you have closed your Terminal and shut down your computer.

This is the very essentials of scripting, the chaining of programs together to create different results. An alias is essentially a one line script.

While it wasn't one of my first aliases I ever wrote, I do have a single alias I will share with you that I use often, it simply invokes timeshift three times, once to delete the old backup, once to create a new backup, and once to list out all backups so I can confirm that the backup was made, I called it tshift, this is the command in my .bashrc:

#.bashrc

#!/usr/bin/env bash

alias tshift="sudo timeshift --delete && sudo timeshift --create && sudo timeshift --list"As you can see, tshift is far less characters to type, and it is a very handy, but very simple, alias I have created for myself. (if you are on Linux and unfamiliar with the sudo command, please see the man pages for sudo, if you are on MacOs, a simple query into your favorite search engine I am sure will yield good results).

Conclusion

Aliases is where I leave this short introduction to the Command Line and Shell. It is at this point that the subject of BASH scripting should be covered, and that is an extensive topic of its own.

I do hope that you have now gained a better understanding and appreciation for the command line and the Shell. The Shell provides a direct, unobfuscated, and elegantly simple interface through which all computer users can accomplish more with less, and is one of the best tools you can become familiar with. So get comfy in it!